- Home

- Bloom, Lisa

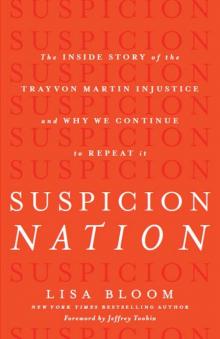

Suspicion Nation Page 8

Suspicion Nation Read online

Page 8

Even if African Americans committed a hugely disproportionate amount of crimes, even if all burglaries at the Retreat at Twin Lakes in the year before Trayvon went out for a walk were committed by black males, it would still be illogical to assume that Trayvon was a burglar. Even though all nuns are Catholic, most Catholics are not nuns, so it would be silly to assume a random Catholic woman is a nun. Even if all burglaries were committed by black males, most black males are not burglars, and it’s equally foolish to assume that a random black male is a burglar.

Why is it so easy for us to understand the former but not the latter? The nuns but not the burglars? The fact that the defense’s logic seemed intuitively right to so many people, yet my nonracial examples are so obviously ridiculous, is a testament to the pernicious “black men are suspicious” stereotype that has long attached itself to the American psyche like a virulent tick.

Lumping Trayvon Martin in with the Bertalan burglars seemed so logical, so rational, so fair that nearly everyone—including the prosecution—just accepted it. Oh, there were some black burglars in the neighborhood? Well, then, we can’t blame Zimmerman for being suspicious when he saw Trayvon.

Oh, yes we can. And much more significantly, we can blame the professionals for failing to object loudly to the racial profiling that was being accepted by everyone in the courtroom about a dead teenager who could not speak for himself.

The prosecution could and should have gone after and dismantled each of the wrongheaded assumptions being fed to the jury about race. One of the first suppositions made by Zimmerman and repeated by the defense at trial that could have been easily destroyed was that many—or most—or at least, a lot (this was never nailed down)—of the neighborhood crimes were committed by African-American males. One got the impression that the neighborhood was overrun by black males breaking and entering homes.

In fact, there is no evidence of that whatsoever. At trial, we only heard about the two Bertalan burglars and then some generalized statements about there being a lot of other crime—but committed by whom? We never learned.

According to an exhaustive review by Reuters,48 in the fourteen months prior to Trayvon’s death, there were eight burglaries and “dozens” of attempted breakins and “would-be burglars casing homes” at the Retreat at Twin Lakes. (Already the data is getting soft, since some of these may have been ill-founded suspicions, as in the case of Trayvon. But we’ll go with these numbers.)

“Dozens” is vague, but let’s pick a low “dozens” number of three, for thirty-six attempted or suspected breakins, plus the eight actual burglaries, for a total of forty-four crimes at the Retreat at Twin Lakes. Three were committed or attempted by black males, says Reuters, the Bertalan burglars plus one more. So, three out of forty-four in our local crime sample were known to be African American. That number would be significantly less than the 20 percent of the population blacks comprised of the Retreat at Twin Lakes, and far less than the 40 percent African American composition of the area surrounding Sanford.

If that’s all there were, one could say that blacks would be less likely to break and enter than members of other races.

But we can’t assume all the unknown-race thieves were white, any more than we could assume the remaining forty-one were black, or Hispanic, or Asian American, or anything else. Most burglars are not known to their victims, as they operate stealthily, arriving and leaving unseen. (The Bertalan burglars, for example, rang the doorbell first, probably preferring to rob an unoccupied home.)

There is no evidence that the neighborhood was awash in black criminality, or even that African Americans were committing crimes there in numbers greater than their proportion of the population. Zimmerman’s fears were not well founded—not reasonable. Wouldn’t that have been worth mentioning?

Squarely addressing the race issue would have meant not only attacking the defense’s fatally flawed reasoning (via cross-examination of witnesses where the race issue was raised, and certainly in closing arguments), but also using the state’s own strong evidence that Zimmerman had a clear pattern of improperly racially profiling African Americans. Because his call to police that night about Trayvon looking like “a real suspicious guy” was not Zimmerman’s first, or second, or third. As the self-appointed neighborhood-watch coordinator, he had called many times before about suspicious-looking men in his community. Guess what percentage of them were African American? Since the population was 20 percent African-American, 40 or 50 percent would be a lot, wouldn’t it?

All of them. One hundred percent of Zimmerman’s calls admitted into evidence about suspicious persons involved African Americans. (Zimmerman had even called the police about a seven-to nine-year-old black boy walking down the street alone, ostensibly concerned for his well-being, even though he was walking toward an elementary school.)

In the first week of trial, the state fought hard outside the jury’s presence to enter into evidence police calls Zimmerman had made in the months before the shooting. Though the judge ultimately granted the state’s request and admitted recordings of these calls into evidence, strangely the prosecution did not use the evidence and remained silent on Zimmerman’s pattern of racial profiling throughout the trial.

Let’s take a look at those calls. Over the eight years he’d lived in the community, the hyper-vigilant Zimmerman made forty-six police calls49 (some were to 911 and some to a nonemergency police line). Audio of only the most recent six were preserved, and five of those were calls about people in the neighborhood he deemed suspicious. (The sixth involved no humans—simply a garage door left open.)

In addition to the April 22, 2011, call about the little African-American boy, Zimmerman contacted the police about these individuals:

♦ On August 3, 2011, a black male wearing a white tank top and black shorts, walking in the neighborhood, whom he called a “match” to a recent burglar, according to his wife’s description. Zimmerman became agitated that the man walked away from him while he was on the call. At the end of the call, he indicated he was going to follow the man, and a woman, probably Zimmerman’s wife Shellie, said, “Don’t go.”

♦ On August 6, 2011, two black teenaged males he said matched the description he’d heard from his wife of burglars in the neighborhood, wearing tank tops, shorts, and jeans, walking near the back gate of the community. Zimmerman told the dispatcher “they typically run away quickly.”

♦ On October 1, 2011, two black males who were “suspicious characters” in a white Impala, mid-twenties to early thirties, at the gate to the community. Zimmerman did not recognize them. He was concerned they were connected with recent burglaries.

♦ On February 2, 2012, a black male in a black leather jacket, black bomber hat, and flannel pajama pants who was walking near the house of a neighbor. “I know the resident, he’s Caucasian,” Zimmerman said.

In a rare moment of a police officer on the case actually investigating Zimmerman’s motives, the lead detective on the case, Chris Serino, noticed Zimmerman’s pattern of racial suspicions. In his formal request to the state that Zimmerman be charged with manslaughter, signed March 13, 2012, Detective Serino noted that “All of Zimmerman’s suspicious person calls while residing in the Retreat neighborhood have identified Black males as the subjects.”50

Detective Serino, a sixteen-year veteran of the Sanford Police Department, was authoritative and credible, an appealing witness whom jurors later praised. He testified at length about his investigation, putting together the jigsaw pieces for the jury as a seasoned homicide detective.

Yet in court, he was not asked a single question about this keen observation he’d made early in the case. The prosecution avoided it like it was radioactive. They did not even let Serino discuss Zimmerman’s racial profiling as one piece of the puzzle. The state’s other major blunder with Detective Serino was allowing the defense to elicit from him his opinion that he found Zimmerman’s selfdefense story truthful. The lead detective believes Zimmerman! That was a big momen

t in the courtroom. The next day, the prosecution woke up and objected retroactively, as witnesses are not permitted to opine on credibility of other witnesses, which is the province of the jury. The judge agreed, and told the jury to strike that powerful testimony from their minds. They didn’t. Juror B37 relied on it in reaching her verdict, she later told CNN’s Anderson Cooper. A better strategy would have been for the prosecution, on redirect (their next chance to question Serino), to show the detective his request that Zimmerman be charged with manslaughter, which demonstrates clearly that he thought Zimmerman should be held accountable for the killing. In other words, he may have initially found Zimmerman credible, but once he’d had an opportunity to review all the evidence in the case, including the strong evidence of Zimmerman’s racial profiling, he wanted Zimmerman arrested. That would have cleared up the issue. But it never happened.

Though the prosecution failed to use the evidence of Zimmerman’s recent police calls about supposedly suspicious African-American men (none of whom were actually doing anything criminal), though they failed to ask a single witness about it, though they stayed away from the subject in closing arguments, a courtroom amateur picked up on Zimmerman’s pattern of racial profiling: Maddy, the juror. The jurors listened to those audio recordings during deliberations, Maddy explained, and she said, “I noticed that all the prior calls about suspicious people were about black guys.” She put together evidence that the prosecution had not put together for her. “Yeah, he profiled him from the beginning,” Maddy said. “The evidence is there. He profiled him because he was black, but the law says that at the end of the day, all that mattered was who was on the top and who was on the bottom.” She didn’t mention the subject in deliberations because she’d been told race was not part of the case. If anyone else noticed it, they didn’t speak up about it either, she says.51

As we saw in Chapter Two, the jury was hopelessly confused about the law of selfdefense, which definitely does not state that in a physical altercation, the person on the bottom can take out a gun and shoot to kill the guy on top.

Here, had the dots been connected for the jury as they should have been in closing arguments, they would have understood that racial profiling was relevant to two key issues in the case. First, did Zimmerman reasonably fear that Trayvon was going to kill him, as he claimed? Recall that reasonableness is an essential element of Zimmerman’s selfdefense case. One who jumps to panicky conclusions every time a black male walks down the street is not reasonable. Zimmerman was not reasonable when he instantly concluded that Trayvon was “up to no good,” a criminal, an asshole. Racial profiling is, to put it mildly, unreasonable. In this case, it was deadly.

Second, one of the elements of the top charge, second-degree murder, was intent. That is, that Zimmerman intentionally killed Trayvon with hatred, spite, or ill will. One who assumes a stranger, even a minor, is a “fucking punk,” a criminal who “always gets away” simply because the stranger is African-American is certainly not behaving with goodwill.

The state fumbled the race issue throughout the trial, most noticeably in prosecutor John Guy’s rebuttal closing argument, the state’s last chance to drive its points home with the jury. Guy insisted forcefully that the case was not about race. Relying on a strategy reminiscent of the film A Time to Kill, Guy asked the jury to consider a role reversal: would Trayvon be convicted if he had followed and then shot Zimmerman? After this obvious, if implicit, reference to race, Guy finished up by reminding the jury that the case was not about race.

Huh?

One of the final photos the defense showed to the jury was a 7-Eleven surveillance camera image of Trayvon an hour before his death, the kind of blurry photo one sees on the local news when the police are searching for a holdup suspect. This was the person Zimmerman encountered, defense counsel insisted.

By the following night, Zimmerman was acquitted. Afterward, smiling broadly after her team had just lost the case, Angela Corey, the special prosecutor, said, “This case has never been about race. But Trayvon Martin was profiled. There is no doubt that he was profiled to be a criminal. And if race was one of the aspects in George Zimmerman’s mind, then we believe we put out the proof necessary to show that Zimmerman did profile Trayvon Martin.”52 It was the same confused babbling about race the state had engaged in during the trial, the same incomprehensible mixed message.

FOUR

Bungling the Science

WITH THE TELEVISION show CSI and its spinoffs, CSI: Miami and CSI: NY, as well as popular crime shows like NCIS and Forensic Files, the crime show juggernaut has taught the public that science—precise, verifiable, dazzling—can solve cases a heck of a lot better than human witnesses. Bestselling author and forensic anthropologist Kathy Reichs has written nineteen popular novels in her Temperance Brennan series, translated into thirty languages, about how forensic science cracks cases and conclusively proves the guilt or innocence of accused rapists and murderers. (The hit TV show Bones is based on her books.) The original in this genre was the bestselling Kay Scarpetta series by Patricia Cornwell, with its female heroine, a smart chief medical examiner for Richmond, Virginia.

And like the television and reading audience, jurors respect forensic evidence, often to the point of awe. What’s not to love? Eyewitnesses err, innocently or intentionally. Science doesn’t lie, right?

While we love shows and books based on crime scene forensics, most Americans’ scientific knowledge comes woefully short. Only 21 percent53 of us can explain what it means to study something scientifically, and the vast majority of Americans are unable to read the science section of a newspaper, which is written for a lay audience.

Into that chasm between reverence for scientific evidence and our own ignorance of the field come expert witnesses, who bridge the gap by using their years of study and experience to explain key aspects of a case to jurors. The right medical expert can make or break a case because the jurors may simply cede the decision to him or her. Ah, the doctor says so, and that settles it. Who am I to say otherwise?

In a 2009 Emory University experiment,54 a group of adults was asked to make a decision while contemplating an expert’s claims, in this case, a financial expert. An M.R.I. scanner gauged their brain activity as they did so. The results: when confronted with the expert, it was as if the independent decision-making parts of many subjects’ brains switched off. They shut down and went with the professional’s recommendation, even if the advice was bad.

Thus, we expect jurors to lean forward in their seats when scientific professionals take the stand, bringing their medical degrees and credibility, their lab reports, their jargon-heavy opinions, their expert analysis that pulls together the facts into one neat explanation of what happened.

But scientific opinion is only as good as the fallible humans presenting it to the jury.

REMEMBER PRIMACY AND recency? Just as movies want to start and end with a bang, lawyers usually want to put their strongest witnesses on first and last, to seal them in the jurors’ memories. The prosecution chose to call its medical examiner as its final witness in its case-in-chief (its primary case; after the defense’s case, a brief opportunity for rebuttal remained). Dr. Shiping Bao, with his twenty-four years of experience in forensic pathology (the study of corpses to determine cause of death), performed the autopsy on Trayvon Martin the day after his death, February 27, 2012. He was there to explain to the jury what his medical review of Trayvon’s remains showed—to speak for Trayvon, in a sense, beyond the grave.

The jury remembered him all right. Months after the trial, at the very mention of Dr. Bao’s name, Maddy laughed: “Oh my God, that man was a hot mess!” At the time he testified, commentators across the spectrum at last found something to agree upon in the controversial case. The medical examiner’s testimony in no way advanced the state’s case against Zimmerman, scored at least one real point for the defense, and was, overall, a fiasco.

To begin with, there was a bit of a language problem. Dr. Bao, a Ch

inese national who immigrated to the United States at age twenty-nine for the “American dream,” spoke with a thick accent, which was sometimes difficult to decipher. But he was aware of it, and so on the stand he overcame that moderate hurdle by speaking slowly, as clearly as he could, and spelling words that he knew might not be properly understood. (Language problems are surmountable. Another Chinese American, Dr. Henry Lee, also speaks with a noticeable accent, is considered one of America’s foremost forensic scientists, and is a celebrity expert witness.)

The bigger problem was that Dr. Bao often appeared unwilling or unable to answer the prosecutor’s questions, preferring to veer off into subject matters that were not being asked of him. By the time of his testimony, at the end of the second week of trial, the jury had become accustomed to the basic rhythm of witness testimony: the lawyer asks the question, the witness answers it. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. No veering off onto tangents, no rambling, no challenging the lawyers. Yet there was Dr. Bao, the state’s own professional witness, who one assumes has done this once or twice, being admonished by Judge Nelson several times to please just answer the questions, and only the questions posed. Dr. Bao came across as unfamiliar with the court rules and at odds with the prosecutor, de la Rionda, who was asking him questions.

Why so much friction between two people ostensibly on the same side of the case—the state’s attorney and the state’s medical examiner? Did they not communicate before Dr. Bao took the stand?

Now we know. A month after the trial, Dr. Bao was fired by the Volusia County Medical Examiner’s Office for his poor performance in the Zimmerman trial. He promptly hired flashy local attorney Willie Gary, whose website’s home page leads with photos of Gary in his white Bentley and seated in a private plane, set to the tune of the theme song from Rocky. A voiceover modeled on “let’s get ready to ruuuumble!” announces that Gary, a personal injury attorney, calls himself “the giant killer” and proclaims that he has won over 150 settlements and verdicts over $1 million. Rather than file suit, Gary promptly took Dr. Bao on a media tour, in which they threatened to sue the county “shortly”55 for $100 million—a headline-generating, astonishing demand in the context of a wrongful termination case, where the typical recovery for a successful complainant is a few years’ pay. (Dr. Bao earned less than $200,000 annually; punitive damages are not available in an action against a government entity, like a county.) At the time this book went to press, no lawsuit had been filed.

Suspicion Nation

Suspicion Nation