- Home

- Bloom, Lisa

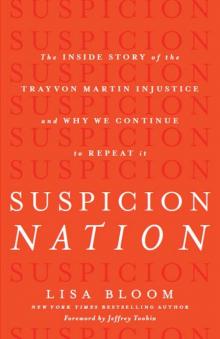

Suspicion Nation Page 25

Suspicion Nation Read online

Page 25

Notwithstanding tragic outcomes like these, the Castle Doctrine, for the most part, is bedrock American law. Its roots go all the way back to before the founding of the United States, to English common law, even the Old Testament: “If a thief is caught breaking in at night and is struck a fatal blow, the defender is not guilty of bloodshed.” (Exodus 22:2). The Castle Doctrine is here to stay. So powerful is the notion that a stranger entering our home is inherently a dangerous threat that we essentially allow homeowners to shoot first and ask questions later. We are willing to accept tragic accidents like these without any calls to change the law.

From the standpoint of the Japanese, or the parents of children who have been shot, the Castle Doctrine is overly expansive in protecting the rights of shooters. It forgives poor judgment, even when the bloodshed that results is the bloodshed of children. So why on earth would anyone want to expand it further?

But that’s precisely what Florida, and then many other American states, did. In 2005, unsatisfied with these broad protections for shooters inside their homes, Florida enlarged the right to use deadly force, without a duty to retreat, to any situation where a person believed she was in grave danger in a place she was lawfully entitled to be present. On the street. In a park, or a car, or an office. Other states quickly followed suit. Twenty-seven states223 now have some form of Stand Your Ground laws, allowing citizens to shoot (or stab, or fight—but mostly shoot) their way out of threatening situations, rather than remove themselves from them.

Stand Your Ground is deeply appealing to many Americans steeped in a culture of sports, war, adventure movies, and violent video games. In our way of thinking, ceding ground in football, surrendering territory on the battlefield, and running away from danger are for losers. Few of us are Mennonites, or Quakers, or pacifists who see true strength in refusing to be baited into violence. Standing one’s ground has a ring of bravery and virility, of film lines that cause audiences to erupt in applause: bring it on, or make my day, or say hello to my little friend (as Scarface pulls out his M-16). A popular T-shirt and bumper sticker after 9/11 featured an American flag with the words, “These colors don’t run,” emphasizing that we are a people who stay put and fight, though no one had suggested we retreat from where we were attacked—America. Each part of Stand Your Ground resonates with these values: stand—plant your feet, don’t run like a coward; your—that turf belongs to you, fight for it!; ground—don’t lose your position, physically or in the argument. No surrender. Man up. Don’t give ’em an inch.

Stand Your Ground.

Like popular culture, Stand Your Ground focuses on who is standing, not who has fallen. In tough-guy movies or video games, gun violence is an exhilarating way to obtain satisfying retribution against a two-dimensional bad guy. The next scene always features the triumphant shooter, not the impact of the shooting death. Messy real-world consequences would only muck up the story line: the life extinguished, the grieving family; the orphaned children scarred for life; the searing loss of a beloved spouse or friend; the hospital, funeral, and burial expenses; the loss of an income earner, reducing a family to homelessness. Twenty years later, Webb Haymaker still thinks of his teenaged friend often, trying to make sense of the trauma he endured witnessing Yoshi’s death. “It’s hard to fully comprehend what it means for someone to die when they’re sixteen years old,” he said224 recently.

With the broad protections of the Castle Doctrine, why was Stand Your Ground needed? Was there a rash of people who’d peacefully extricated themselves from threatening situations on the street and later regretted it, thinking, “If only I’d stayed put and killed that guy. Unfortunately, I was well versed in the law and knew that would not comply with the rules regarding selfdefense. So now I must go to my legislator and get a bill moving so that next time I’m in a perilous encounter, it can end with satisfying bloodshed”? No, that never happened.

According to a symposium225 of prosecutors, law enforcement, government officials, public health advocates, and academics assembled from a dozen states by the National Association of District Attorneys, who exhaustively reviewed the history and status of nationwide Stand Your Ground laws, the impetus started with 9/11. One of the repercussions of the worst terrorist acts on American soil was increased fear—fear of sudden attacks by extremists, fear of crime, fear that law enforcement would not necessarily be able to respond quickly enough if another 9/11 happened. That generalized anxiety morphed into advocacy for the right of citizens to be armed and ready to protect themselves at any time from threats foreign and domestic, without worry about criminal prosecution. Since 9/11, the gun rights lobby expanded the rights of citizens to own guns, even formerly banned assault weapons, and to keep them not just in the home but holstered on the body as one goes about one’s business. And hand in hand with those expansive gun rights went Stand Your Ground laws, which increase the opportunities for citizens to not just own but to use those guns.

Of course, a civilian with a handgun, or ten or a hundred or a million civilians with handguns, or even high-powered rifles or automatic weapons, would have been entirely ineffective against airplanes being used as missiles, unless those armed citizens were passengers on the 9/11 planes. Even the NRA does not advocate arming air travelers. But the apprehension remained, and it motivated a variety of ill-advised legislation, like the Patriot Act, which restricted civil liberties and allowed for previously illegal detentions, wiretaps, eavesdropping, and searches (several portions of the law have been struck down as unconstitutional), and Stand Your Ground laws.

Fast-forward to 2012. A month after Trayvon Martin was killed, the police were saying they could not arrest Zimmerman due to Florida’s Stand Your Ground law, and the public was in an uproar. Florida Governor Rick Scott convened a nineteen-member Citizen Safety and Protection226 task force to review the law. After its review, the bipartisan task force recommended no change in the law and concluded, “Regardless of citizenship status, (people) have a right to feel safe and secure in our state. To that end, all persons have a fundamental right to stand their ground and defend themselves from attack with proportionate force in every place they have a lawful right to be and are conducting themselves in a lawful manner.”

And that, ultimately, is what Stand Your Ground is all about. That feeling of safety, that gut sense that we all have a fundamental right (so fundamental that until a few years ago, no one had even thought of it) to defend ourselves with force, even if it’s not really necessary, even when walking away would prevent injury, mayhem, or death. Even if that feeling of safety, of the rightness of meeting violence with more violence, demonstrably results in more injuries and deaths, and more killers walking the streets, immunized, armed, and ready for the next altercation. To supporters it just feels right, and that’s good enough.

The second justification for Stand Your Ground laws was that they were seen to go hand in hand with gun rights. In Florida, by 2005 the NRA had already persuaded the legislature to enact a sweeping set of gun rights laws,227 granting access to firearms to most citizens over the age of twenty-one. Floridians may purchase guns without any licensing or registration. For the gun lobby, Stand Your Ground was the next logical step. Why allow so many people to carry guns if they can’t fire them?

Stand Your Ground laws have typically been enacted over the strenuous objections of law enforcement, who understood that loosening selfdefense rules leads to more shootings and less accountability. In other words, lawlessness. And the professionals on the ground were right. Stand Your Ground states have seen a doubling of justifiable homicides—killings where the shooter has no legal responsibility and usually is not even charged with a crime at all. In Florida, justifiable homicides doubled within two years after its Stand Your Ground law was passed. By 2011, the numbers tripled.228 Justifiable homicides remained flat or decreased in states without the law. This reflected the nationwide trend, as justifiable homicides by civilians using firearms doubled in states with Stand Your Ground laws between

2005 and 2010,229 while falling or remaining about the same in states lacking them.

Proponents argued that more “good people with guns” on the streets would reduce violence, as criminals would know they could be stopped by any citizen at any time. Yet the reality is that since 2005, Florida’s Stand Your Ground law has allowed killers to go free where the facts of the case previously would have made that unthinkable. The Tampa Bay Times conducted a thorough examination of seven years of criminal cases where defendants claimed they should not be prosecuted due to their new Stand Your Ground rights. The results showed that Florida prosecutors, judges, and juries had exonerated killers230 whose victims were in retreat and were shot in the back, killers who picked fights with their victims, and killers who left the scene of an altercation to get a gun and then returned with it to fire the fatal shots. One Florida judge,231 Terry P. Lewis, complained that Stand Your Ground could be used to exonerate everyone in a Wild West–style shootout on the street, as they could all claim they were reacting to the others, with no duty to retreat. He said he had no choice but to grant immunity from prosecution to two gang members who had fired an AK-47 assault rifle that killed a fifteen-year-old boy.

As with so much else in our criminal justice system, African Americans fare worse, much worse, under Stand Your Ground. According to a study by the Urban Institute’s Justice Policy Center, in Stand Your Ground states, whites who kill blacks are 354 percent more likely to be found justified in their killings. Similar studies232 have also found that those who shoot black victims are far more likely to be exonerated than those who shoot members of other races. As we’ve seen, in considerations of whether a victim was threatening, African Americans are judged more harshly, their behavior perceived as aggressive where the identical behavior from a white person is not. Those subjective determinations are constantly at play in Stand Your Ground cases, often with only the word of the shooter to go on after the smoke has cleared. In other words, if you’re going to shoot someone on the street and claim selfdefense, it’s a huge advantage to be white. Whites who shoot blacks are the most likely of all to be acquitted (actually, they are unlikely to even be charged).

Stand Your Ground laws immunize the shooter not just from criminal prosecution, but also from civil suits for financial compensation for the victim’s next of kin. Stunningly, this is broader than the rights of the police, who are immune from neither prosecution nor lawsuits when they injure or kill citizens in the line of duty.

America’s new round of Stand Your Ground laws run entirely in the wrong direction, encouraging more violence, protecting shooters from responsibility for their decisions to take lives, amplifying the lack of accountability when whites shoot blacks. The old thinking was that gun deaths on our streets were a social evil that the law should make every effort to deter. The new thinking: we’ll tolerate more firearm fatalities in order to feel better about crime. Stand Your Ground laws are more appropriately called Shoot First Laws (as the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence calls them) because they bestow such powerful legal advantages on whoever shoots first in an altercation. The preservation of human life is no longer our paramount concern.

THE STAND YOUR Ground defense was officially not part of the Zimmerman murder trial, until it was. That is, shortly before the trial, the defense announced233 that it would not invoke Zimmerman’s rights under the law because his account was that he was restrained at the time he fired the shot, unable to escape. Retreat was impossible, according to Zimmerman’s story, and hence the law did not apply to the facts of the case. During the trial, neither side argued that the Stand Your Ground law applied or didn’t apply—it was a nonissue.

But then a curious thing happened. The language crept into the jury instructions. On page twelve of all the legalese, Judge Nelson included this sentence:

If George Zimmerman was not engaged in an unlawful activity and was attacked in any place where he had a right to be, he had no duty to retreat and had the right to stand his ground and meet force with force, including deadly force if he reasonably believed that it was necessary to do so to prevent death or great bodily harm …

And Stand Your Ground was part of the jurors’ decision making as well. Juror B37 said that Stand Your Ground was part of the law the jury considered in reaching its verdict. “The law became very confusing. It became very confusing,” she told Anderson Cooper on CNN. “We had stuff thrown at us. We had the second-degree murder charge, the manslaughter charge, then we had selfdefense, Stand Your Ground.”234 Later in the interview she said that Zimmerman was acquitted “because of the heat of the moment and the Stand Your Ground.” (“Heat of the moment” was also not a defense in the case.)

How is it possible both that the defense disavowed Stand Your Ground and that the judge and jury included it? For the judge’s part, she simply used the standard Florida selfdefense instruction, which since 2005 includes Stand Your Ground language, whether the defendant invokes it or not. As to the jury, the answer is murkier. Stand Your Ground had been part of the public discussion in Florida, and especially the media coverage of the Trayvon Martin shooting. Floridians knew that they had the right to stand their ground and fight, even if none of the lawyers argued that as a defense in the courtroom. At any rate, there it was in that confusing booklet they took into the jury room.

In the Trayvon Martin case and in many cases, Stand Your Ground has become a proxy, shorthand for the concept that altercations can turn deadly without any legal accountability. In Stand Your Ground states, juries no longer have to parse the issue of whether there was a reasonable escape route, whether a life could have been saved by a citizen de-escalating a volatile situation. Diplomacy and nonviolence are no longer valued, or required. More broadly, Stand Your Ground is understood as a rule allowing citizens to pull out a gun and shoot in any fight, even if that’s not the law.

The solution lies in returning to our shared value that the preservation of human life must be paramount, and the recognition that laws that do not facilitate that goal do not serve us. We cannot accept more killings, more street deaths, more shooters walking free, emboldened for the next time by the law that’s got their back. “Feeling better” is an insufficient justification for laws that increase deaths, and how on earth do we allow ourselves to feel better about more violence anyway?

Labor organizer Cesar Chavez said, “In some cases nonviolence requires more militancy than violence.” In a culture that does not find restraint sexy, we must nevertheless demand that everyone behave like adults in hostile confrontations, and we must punish those who cannot. We must return to our law’s strict insistence upon nonviolence whenever humanly possible. Shooters should know that their actions will be carefully scrutinized by authorities. The repeal of Stand Your Ground would return us to that civilized rule of law.

CONCLUSION

Aligning Our Actions With Our Core Values

“Things don’t happen. Things are made to happen.”

—PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY

WIDESPREAD IMPLICIT RACIAL bias, the enthusiasm for unrestricted gun ownership, and expansive Stand Your Ground laws combine to enable the continued shootings of African-American young people who are taking out the trash, knocking on a door, or stopping at a gas station. It’s no longer just the police who are accused of racial profiling. A prolifically armed citizenry now stands ready to back up its suspicions with gunfire.

Individually, each of these three problems causes enormous harm. Unreasonable fears of “blacks as criminals” underlie the rampant discriminatory treatment of African Americans in our criminal justice—justice—system, the one place where fairness should be paramount. Even in our schools, where we should be educating children and correcting their immature mistakes, giving them skills for success, we push out and lock out black kids punitively, jacking up their odds of failure, cycling another generation into poverty. The fact that we have fifty million more guns than cars in the United States, with next to no requirements that gun owners be qualif

ied to possess them, means that day after day, those firearms are used carelessly to snuff out the lives of Americans of all races and ages, as the rest of the civilized world looks on with horror. And Stand Your Ground laws not only embolden gun owners to use their weapons even when they could have ended the incident peacefully, they then immunize and exonerate killers, bestowing on them a feeling of impregnability for the next time. (After his acquittal, George Zimmerman’s wife Shellie said he felt “invincible.” Why wouldn’t he?) No longer required to call the police, citizens become the law themselves, deciding based on a hot stew of suspicions and fears and snap judgments, finger on the trigger, that shooting is the best option. Afterward, when the deceased turns out to be unarmed and it was all a misunderstanding, no remedy follows. No justice for the victim’s family. Not even compensation.

We have veered away from our core values. Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” When those lofty words were written, they could not have been further from reality. They expressed where the founders saw us going, not where we were at the time. Equality of all persons was hardly self-evident in the slave days of the eighteenth century, when only property-owning white men had any real legal rights. Jefferson’s words were a promise, filled with unrealized potential, a check waiting to be cashed. A century later, after the mass carnage of the Civil War ended slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment was passed, guaranteeing each citizen the constitutional right to “equal protection of the laws.” Those words too were more hope than truth, as segregation and the legally enforced discrimination of the Jim Crow era continued for another century still. The twentieth century saw the aspirational 1954 landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, in which the U.S. Supreme Court declared public education as “a right which must be made available on equal terms,” and passage of the groundbreaking 1964 Civil Rights Act barring job and housing discrimination based on race (and other factors), legal advances we could all feel good about, though glaring disparities in education, employment, and housing continue in earnest to the present day. And meanwhile, rampant racial inequality desecrates our criminal justice system, wholly unchecked by the law.

Suspicion Nation

Suspicion Nation