- Home

- Bloom, Lisa

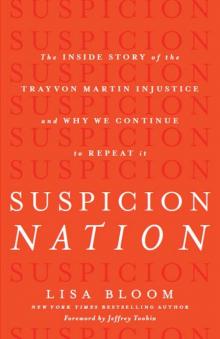

Suspicion Nation Page 2

Suspicion Nation Read online

Page 2

A verdict that could have provided accountability, vindication, and healing did not happen. But we are a nation of laws. The outcome would have to be accepted if the trial was fair. The community would have to just move on if Zimmerman’s acquittal was based on the evidence at trial.

But that was not the case. Because the same suspicions and unexamined biases that Zimmerman harbored in one way or another coursed through the significant players in that courtroom: the defense attorneys, prosecutors, judge, and jury.

BEFORE AND AFTER each day in court, tensions mounted between the jurors. “I had never looked at myself by color before,” Maddy said. “The more we think about differences and negativity the more situations we have like this.” She didn’t think of herself as a minority. Months after the trial, she struggled with the question of whether she identified as Hispanic, black, or both. (“Hispanic,” she settled on, but she also considered African Americans as members of “my culture.”) But whatever category she belonged to, the trial and the behind-the-scenes group dynamics reminded her constantly that she was different, “other.” The five white women seemed to inhabit another world.

A class divide, too, loomed large. Maddy bristled when other jurors complained about hotel housekeeping, for example. She identified more with the maids, a job she’d once had, than with the women she was sequestered with who griped about their service. One of the other jurors grumbled that she had no towels. “I gave her my towels,” Maddy said, exasperated. “I only need one towel. I don’t deal with face towel, hand towel. I have one towel. A towel’s a towel, no big deal.”

Other jurors told her to stop making her own hotel bed each morning. “Let the maid do it!” Maddy shook her head at the memory. “Do you really think a woman who has eight kids, who’s worked her whole life, doesn’t want to make her own bed? I used to work at Red Roof Inn, I had twenty rooms a day,” Maddy said with pride. “I can make my own bed, clean my own room. If I can make that woman’s life easier, I’m going to do it.”

To some of the others, that was so funny!

After a group restaurant meal, Maddy wanted her uneaten food wrapped up for later. The other jurors teased her and told her not to—all their meals were being paid for by the state, so why save leftovers? Wasting food was anathema to Maddy. She couldn’t do it. “I couldn’t tell them I’d lived in a shelter with my kids, that I got some government assistance, that I’ve had a hard life. What would they think of me?”

Maddy didn’t want to believe it, but the racial and class differences seemed to pop up everywhere in their daily interactions. “It’s not about color, it’s about how people are raised,” she often says. Yet even in the TV room, the one safe space for the jurors to relax after stressful days in court, the gulf between Maddy and her fellow jurors widened. There the jurors watch monitored television shows and movies in the evenings and weekends, yet the group elected to watch shows with predominately white casts that Maddy disliked and even found offensive. HBO’s blood-soaked, sexually explicit Game of Thrones was the group’s favorite, and they watched it constantly. The violence and nudity disgusted Maddy: “I couldn’t see it,” she said. She’d asked to watch some of her beloved reality shows, like Bridezillas. “It’s mostly white people on that show so I figured they would like it,” she said, but the group vetoed it, on the grounds that it was “so dramatic.” Bad Girls Club was one of Maddy’s favorites, a popular reality show featuring a multiethnic group of aggressive, quarrelsome women living together in a luxury mansion, “but I knew they wouldn’t go for it,” she said. “I didn’t want them to think I was ghetto and covering it up. I was trying to fit in.”

One of the other jurors assumed control of the remote from the beginning and took it upon herself to decide what the group would watch. Maddy was granted one request for one thirty-minute show in three weeks, Bridezillas. No one could understand why she enjoyed it. As a result, Maddy removed herself from the social setting of the TV room, preferring the isolation of her room.

They weren’t all bad. Just different from her. There were moments of kindness, certainly. A well-meaning fellow juror gave Maddy a music CD to listen to, telling her she’d probably like it since it was in Spanish. “It wasn’t Spanish. It was French!” Maddy told her, returning the CD.

“I felt very alone,” Maddy said. She felt small compared to the other women. “I’m in this bubble, I’m inside with these women. Everyone was talking about what they’ve done with their lives, how important they’ve been, and all I had to talk about was me and my kids because that’s my life. I didn’t sound too important. There wasn’t too much interest in me from the other women. So I stayed in my room.” There she would read her Christian books, like one by African-American megachurch bishop T.D. Jakes. She’d also do puzzles, and color in coloring books. The only bright spot in the calendar for Maddy was on Sundays, when her kids and husband would visit for one hour, with a sheriff’s deputy sitting near her door.

Was it just a coincidence that Maddy’s room was the only one with an officer stationed just outside? She couldn’t tell. Did they see her as suspicious? She wondered. “I go to a lot of places and they get people to follow me sometimes,”9 she said, recounting the common experience of Americans of color.

The juror designated as B37 treated Maddy the worst. (Maddy’s the only one who’s used even her first name in post-trial interviews. Her last name is withheld here to protect her privacy.) Early on in the trial, Maddy had called ramen noodles “Roman noodles,” and B37 ridiculed her mercilessly. “You talk so funny!” All the other jurors laughed, and at first Maddy laughed uneasily along with them. Then she realized, They’re not laughing with me, they’re laughing at me. B37 referred to “they” or “them” a lot, Maddy said, and she knew who she was referring to. People like her.

“I didn’t know I didn’t speak proper English,” Maddy said, until B37 kept making fun of Maddy’s word choices.

Several of the white jurors were animal lovers. “We can’t afford a dog,” Maddy said, but she “respect[s] that love.” As the trial wore on, one juror made a special request, which was granted, to spend an entire weekend day with her dog. The dog was brought to the hotel and she enjoyed nine hours with him.

Maddy, aching for her children, thought that if the dog visit was granted, she should have a full day with her baby, rather than one hour per week, which felt so brief. “I would have loved nine hours with my baby,” she said. She summoned her courage, spurred on by another juror, and made her request, which was denied on the ground that children can talk. Her infant daughter was three months old. (She was granted just one extra hour with her baby on Sunday.) Maddy’s belief that she was singled out for different treatment continued.

By the final week of trial, “I felt I had no voice,” Maddy said. “My voice had been taken away. No matter what I would say it wouldn’t make a difference. I was not important.” On Monday, Maddy had uncharacteristically failed to come out for her telephone call with her family. Later, she emerged from her room, crying. A kind deputy asked her gently why she had not come out earlier. “I am going through a lot,” Maddy said, and he seemed to implicitly understand. “Only those who come from my culture understood my pain,” Maddy said.

The deputy made it clear that Maddy needed to stay on the jury. He sat with her and talked about his kids. He told her he had just become a law enforcement officer, and that his wife was a lawyer. “I’m African American,” he told her. “For other people this comes easy.” But he’d had to work hard, stay strong. That resonated deeply with Maddy. Here was someone who got it, that feeling of difference. He talked about his pride in his job, and what he had overcome to get there.

“That man inspired me so much,” Maddy said. “I prayed for him, asking God to bless him financially, physically, mentally. He made me feel he’s here to protect all of us, no matter what color. I kept strong and stayed with it to show people what I could do.”

But three days later, on Thursday of the final week,

Maddy was losing it again. She didn’t realize the trial was almost over. For her, it felt like an endless pressure cooker, and she wanted to get out. B37 was back at it, insulting Maddy for the way she spoke, and now, mocking another juror for drinking more than her allotted two glasses of wine or beer per day (“you shouldn’t be drinking because you don’t know how to act when you drink”) or making rude comments about another juror’s disabled child. “I swear to you, you seriously have to stop talking,” Maddy told her. “If you have nothing positive to say, don’t talk to me. You need to stop talking about people.”

The stress was too much. Maddy broke down crying and again decided she had to go home. Another deputy, a Hispanic woman, came and spoke to her. “Why am I being abused?” Maddy asked. “Why do I feel so bad?” She felt again that she had no voice, that she was always drowned out by the others, that “whatever [she] said wasn’t going to matter.” This deputy too insisted that she stay. She soothed her, telling Maddy she was almost done, pleading with her not to go. She could do it. She needed to do it. Ultimately, the officer convinced her to stay, hugging Maddy, listening to her, and “making me feel important.”

The isolation, the shunning, was almost more than Maddy could bear, but the efforts of these two sensitive deputies, whom Maddy felt comfortable with, kept her there.

Closing arguments and then deliberations on Zimmerman’s fate began the next day. In her heart, Maddy believed that he should be convicted of second-degree murder, the top charge.

But two other jurors, who strongly favored acquittal from the beginning, seemed to know so much more about the facts and the law than she did. That feeling of naiveté and ignorance overwhelmed her. One juror would mention that she knew things about the case that hadn’t come up at trial, and that she had a lawyer for a husband; another juror’s son was a lawyer too. These two seemed to understand the law far better than Maddy did. They possessed an authority that Maddy couldn’t begin to counter.

For a layperson like Maddy, the inconsistent, long-winded legalese found in the booklet of jury instructions was impossible to fathom, much less follow. “For them to tell me to make a decision on someone’s life, and then to give me a whole booklet that I couldn’t understand … I don’t understand,” Maddy said, still puzzled and disturbed months after the conclusion of the trial.

How could Maddy persuade the others to convict? What resources could she draw upon? Just her heart and her sense of justice. Three others wanted to convict at the outset too, but as the hours wore on, and they reviewed the evidence, and the pro-acquittal jurors were so sure of themselves, Maddy felt defeated. She couldn’t find the evidence, or the law, to show them that Zimmerman was guilty.

When she discusses deliberations, Maddy talks a lot about her heart. “I went in there wholehearted,” she says, yet, “I listened to the lawyers when they said don’t use your heart. That to me meant he was not guilty.”

She admired the prosecutors for having a lot of heart and appearing to care deeply about Trayvon and his family, but “then they tell me to take the emotion out of it. Wow, that’s all [they] gave me! That jacked me up!”

“The other women were talking a different language,” Maddy explained. Justifiable homicide, Stand Your Ground, manslaughter—these legal terms were unclear to Maddy. “All their points were so educated. It didn’t matter what I said.”

“They knew I didn’t know anything about the law,” she said. What had been an advantage during jury selection—Maddy was the proverbial blank slate lawyers wanted, coming into the trial with almost zero knowledge of pretrial publicity or the rules of the game—now felt like a crushing disadvantage, as the other jurors insisted they knew aspects of the law or other important facts that had not come in at trial but that they’d seen on the news. Should she have studied for the trial beforehand?

As the hours went by, Maddy had the sinking feeling that the verdict she knew was right—guilty—was evaporating. The jurors fought. They wept. Maddy locked herself in the bathroom. She sat on the floor and cried. Another juror insisted she would fight for a conviction to the end. She could not let Zimmerman go without finding him guilty of something.

After ten hours of deliberation they took their first vote. Maddy, crushed, voted not guilty, along with another juror who’d initially wanted to convict. Two more continued to hold out for conviction, but Maddy knew it was hopeless. Eventually, after several more hours, the strong voices for acquittal had persuaded all the others. One “knew more than we knew,” from the pretrial publicity, Maddy says. She knew that “Trayvon Martin was a bad kid,” though no evidence of that had come into trial. She knew that Trayvon was “intentionally behind Zimmerman, that he knew he was going to hit him, and that he planned his own death.” Maddy didn’t know what to believe, or how to respond.

In the jury room, Maddy had been persuaded of several gravely incorrect understandings of the law as applied to the case. “They told me not to look at the beginning [where Zimmerman followed Trayvon], just the fight.” She thought that “you are able to use force when force was used,” and that “the law says that at the end of the day all that mattered is who was on top and who was on the bottom.” (Actually, there is a great deal of legal significance attached to the run-up to the shooting. The rules for using deadly force are far more rigorous than that gross oversimplification, and all the circumstances should have been taken into account.)

Toward the end, the jury sent out a note to the judge asking for an explanation of one of the two charges against Zimmerman, manslaughter. The judge answered only that they needed to ask a more specific question. They were stumped and didn’t want to embarrass themselves with another dumb question, so they didn’t respond. Ultimately Maddy walked away with an outrageously incorrect view of the law, that manslaughter required that “when [Zimmerman] left home, he said, I’m gonna go kill Trayvon Martin.”10 (No, that would have been first-degree murder, which Zimmerman was never charged with.)

“I felt in my heart he was guilty to the end, but I couldn’t prove it,” Maddy said, dejected. Those weeks on the jury left her shattered. When she got home, she fell apart. “I literally fell on my knees and I broke down, my husband was holding me, I was screaming and crying and I kept saying to myself I feel like I killed him.” Shortly after the trial, Maddy began psychotherapy for the first time in her life. “I feel that I was forcibly included in Trayvon Martin’s death. I carry him on my back.” Guilt consumed her. “I’m the only minority,11 and I felt like I let a lot of people down.”

But her faith centered her. “George Zimmerman got away with murder,” Maddy said, “but you can’t get away from God.”

She tried to return to work at the nursing home, but her supervisor told her not to come in for a few weeks after the trial “to let things die down,” and after that, no one there would return her calls. Unable to find another job, and with her husband out of work as well, Maddy and her family moved away from the warm Florida sunshine she had grown to love and back to inner-city Chicago. As this book went to press, Maddy and her family were homeless, staying temporarily with a friend.

Maddy tries to stay positive, but the experience scarred her. “I never experienced being treated as inferior before.”

I WATCHED THE Zimmerman trial from a very different vantage point than Maddy. Having closely scrutinized many hundreds of high-and low-profile murder trials for Court TV, CNN, ABC, CBS, NBC, and other networks for nearly two decades, and having been a trial attorney since 1986 (I still maintain an active law practice), I understand how trials play out in American courtrooms. As a legal analyst, I’m interested almost exclusively in one thing: following the evidence. All of the evidence, to its own conclusion, whether that outcome is popular or unpopular.

Brought in to follow the Zimmerman trial intensively as a special project for NBC News and MSNBC, my assignment was to watch the entire proceeding, gavel-to-gavel, and to report fairly and accurately on what was going on in the courtroom. Watching sound bites or

reading summaries would not cut it. In a case of this prominence, I wanted to watch it all, every minute, and my networks agreed. I had no preconceived notions as to who should win, and I went in with an aggressively open mind. I knew that a trial is an entirely different animal from an arrest. Too many innocent people are convicted in this country. I had previously written about our culture of mass incarceration, a social evil fed by too many young men (often black or Hispanic) railroaded by overzealous, overcharging prosecutors, unaided by overburdened public defenders. Our harsh penal system devastates the lives of these (predominately) young men as well as their families and communities, as we continue to incarcerate more of our own people than any other country on earth, or in human history. It’s a subject I speak about often on television and radio, most recently praising reforms of “mandatory minimum” drug laws that impose long prison sentences on low-level, nonviolent offenders. I did not want to see another of our citizens incarcerated unless he truly belonged behind bars, not in the Zimmerman case, not in any case. Certainly those committing violent crimes like murder or manslaughter should be locked up, but only if the evidence conclusively establishes guilt. Our criminal justice system has its flaws, but requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt is not one of them.

Pretrial, I was uneasy that Zimmerman’s arrest may have been made solely on the basis of the massive community outcry that preceded it, because a criminal trial is almost never the place for resolution of social or political grievances. While many were gunning for a conviction before the first witness testified, I found that unseemly, at odds with our obligation to find proof beyond a reasonable doubt or acquit. Racial profiling, Stand Your Ground, our gun laws—these are all serious social issues, crying out for public debate and reforms (as we shall see in Part Two). But inside the courtroom, the case was about George Zimmerman and Trayvon Martin and what happened during the few minutes of their encounter within the gates of the Retreat at Twin Lakes, where the incident occurred, when Trayvon was walking back to watch the All Star game with a seventh grader and Zimmerman was doing his Sunday grocery run to Target. Let me hear the witnesses. Show me the evidence. Let the chips fall where they may.

Suspicion Nation

Suspicion Nation