- Home

- Bloom, Lisa

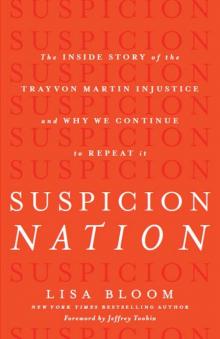

Suspicion Nation Page 16

Suspicion Nation Read online

Page 16

A month after he was accused of shoving the police officer, in August 2005, Zimmerman’s then-fiancée alleged domestic violence and sought a restraining order against him. He responded by seeking a restraining order against her as well, and both were granted.95

Neither of Zimmerman’s prior incidents of alleged violence came in to his murder trial, where he sat throughout, preternaturally calm.

ACCORDING TO HIS brother,96 Zimmerman now wears a bulletproof vest and a disguise whenever he goes out, and he never leaves home without carrying a concealed gun on his person and at least one other firearm in his car. “There’s even more reason now, isn’t there?” said his lawyer, pointing out that Zimmerman is eyed warily by people who recognize him wherever he goes.

Ironically, it is now Zimmerman who is viewed as the real suspicious guy.

IS FURTHER LEGAL recourse against Zimmerman possible? Trayvon’s family could bring a civil case against Zimmerman, similar to the action the estate of Nicole Brown Simpson successfully brought against O. J. Simpson in 1997 after he’d been acquitted of murder in his criminal trial. But civil lawsuits result in money damages only, and Zimmerman has few resources. The U.S. Department of Justice is reportedly investigating whether Zimmerman could be charged with federal civil rights violations, as happened in the Rodney King case in 1992 after four police officers were acquitted in state court despite the fact that their beating of King, an African-American unarmed motorist, was captured on videotape. As time ticks on, and those charges are not forthcoming, the possibility seems increasingly remote.

The Florida criminal justice system offers no recourse for the prosecution’s shortcomings in this trial. “Ineffective assistance of counsel” is a legal theory that defendants sometimes use to get trial convictions reversed, when their lawyers are incompetent. It does not apply to prosecutors. There is no legal remedy for crime victims who believe the state failed them in bringing a killer to justice.

The Double Jeopardy clause to the U.S. Constitution means that Zimmerman can never be retried for the crime of murder or manslaughter for killing Trayvon, even if new evidence emerged, even if he confessed, even if new prosecutors wanted to take a fresh look at the case. The state cannot appeal his acquittal.

THE TRIAL IS over, and despite Corey’s blithe proclamation, the system did not work. And as long as the root causes of the shooting of Trayvon Martin and the acquittal of George Zimmerman remain unexamined, the injustice lingers. That’s why for many, particularly in the African-American community, it’s not over, not even close. Since the Trayvon Martin shooting, more unarmed young black Americans have been shot and killed by whites who instantly and unreasonably feared they were criminals, as we shall see. The shootings continue. Justice remains elusive. Maddy wants to move forward now and is willing to speak out about her experience in the hope it will be used to change the law so that in future cases, jurors like her who know in their hearts that a murder was committed will have the law on their side. Though this case could have been won based on existing law, in the bigger picture, she’s right. Laws are created by us, in an effort to achieve fairness and accountability, and those laws should be reformed by us when they aren’t working. And Stand Your Ground and gun laws are ripe for review.

But truly confronting this disturbing trial and verdict requires more than legal reform. Because getting convictions after racially profiled young people are killed is not the real solution. Saving those lives before they’re gone is. And to prevent future tragedies, we need a new, unflinching look at the uncomfortable issue of race, staring down the buried biases of a nation that so often determine whom we deem suspicious and why.

PART TWO

FEAR AND LAWLESSNESS IN SUSPICION NATION

“Please use my story, please use my tragedy, please use my broken heart to say to yourself, ‘We cannot let this happen to anybody else’s child.’”

—SYBRINA FULTON, MOTHER OF TRAYVON MARTIN

TRAYVON MARTIN’S DEATH was not a tragic accident, unforeseeable, unstoppable, as though an asteroid had smashed into the earth without warning, taking a life. Human-made stereotypes and laws created all the conditions that led to the death of Sybrina Fulton’s son and that made George Zimmerman’s acquittal by far the most likely outcome. Those biases and legal rules remain in effect, polluting our behavior as we interact with our neighbors, impeding just results when those interactions turn violent. At the root of all of it is fear—overblown fear of crime, inordinate fear of strangers, deep-seated fear of difference, and in particular, lingering, unspoken fear that African Americans are criminals. So many of us are suspicious. We eye each other cautiously. And in twenty-first-century America, that fear is often armed, locked and loaded. And so, the body count continues to rise in an atmosphere of increasing lawlessness.

Three months after the shooting of Trayvon Martin, John Spooner, an elderly white resident of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was convinced that his thirteen-year-old African-American neighbor Darius Simmons was a burglar who had stolen his cache of shotguns a few days earlier. As Darius and his mother collected their family’s garbage cans from the curb, Spooner confronted the boy, gun in hand. Darius put his hands up, and his mother asked Spooner “why he had that gun on my baby.” Security footage shows that the boy quickly moved back, and then Spooner shot him once in the chest. As Darius turned and ran, Spooner fired a second shot at his back. He tried to fire a third shot, but his gun jammed. Darius ran a little further, then collapsed and died in the street in his mother’s arms. Darius’s home was searched immediately after the shooting. No guns were found. At his trial, Spooner showed no remorse and said that he also had wanted to kill Darius’s older brother, who had run into the street to help Darius after the shooting. Spooner testified that his shooting of Darius was “justice,” and that “I wanted those shotguns back. They were a big part of my life.” (Spooner was convicted of first-degree intentional homicide, largely due to the videotape from his own security cameras, which depicted him going after the child without any pretense of selfdefense.)

Nine months after the shooting of Trayvon Martin, four black teenaged boys were in a car stopped at a gas station in Jacksonville, Florida. Michael Dunn, forty-six, complained about the loud music emanating from the boys’ SUV, and a verbal exchange followed. Dunn, who is white, says he thought the boys had a gun, and so he opened fire into their vehicle, killing Jordan Davis, seventeen. Jordan and his three friends, it turned out, were unarmed. After the shooting, Dunn went to a hotel, ate pizza, and went to sleep. He was arrested the next morning, two hours away from the crime scene. In a letter written from jail as he awaited trial for first-degree murder and three counts of attempted murder, Dunn called his shooting victim a “thug.”

Eighteen months after the shooting of Trayvon Martin, Jonathan Ferrell, twenty-four, was driving home at 2 AM in Charlotte, North Carolina, when he crashed his car, causing him to climb out the rear window to escape. He went to a nearby house and banged on the door to summon help. The white woman inside, afraid, called 911. Police arrived and Ferrell ran toward them. A white police officer fired twelve shots at him, hitting him ten times. Ferrell’s fiancée said, “I feel like if somebody had just taken a step back and really figured out what was going wrong with him, they would have known he didn’t cause a threat to anybody.”

Ferrell, an African-American football player for Florida A&M University, died instantly that night, September 14, 2013. He was unarmed, had no drugs in his system, and had only a small amount of alcohol in his blood, less than the legal limit permitted for driving. The officer was charged with voluntary manslaughter.

Twenty months after the shooting of Trayvon Martin, another tragedy occurred in a suburb of Detroit, eerily similar to the Jonathan Ferrell shooting that preceded it. In Dearborn Heights, Michigan, nineteen-year-old Renisha McBride’s car had broken down and her cell phone had died. After knocking on a door for help at 4 AM, McBride, who was African-American, was fatally shot in the face by a fifty-fou

r-year-old white homeowner who feared she was a burglar. Prosecutors say the homeowner, Theodore Wafer, opened his front door and fired through his locked screen door. “I can’t imagine in my wildest dreams what that man feared from her to shoot her in the face,” her mother, Monica McBride, said. “I would like to know why. She brought him no danger.” For nearly two weeks, no arrest was made, though the shooter was known immediately and McBride, while inebriated, had no weapon. After community outcry and national media attention, Wafer was charged with second-degree murder, manslaughter, and felony firearm possession.

Stories like these—showcasing overblown suspicion of unarmed African Americans; fear of crime; children or young adults gunned down, often with a lack of accountability or outrage—persist. Racial profiling by police officers continues too, and is sometimes defended, though many police departments have made efforts to diversify and train officers to look beyond race. But how do we address shootings by ordinary citizens? What reordering of our culture and laws is necessary to protect and preserve basic human life?

American media performs well when covering breaking news and dramatic events that capture the public’s attention, like a high-stakes murder trial. It has far less interest in digging deep into the root causes of these horrendous stories, and it often perpetuates the very stereotypes that lead to the tragedies it covers. And so the stories recur, and we remain shocked, stunned, saddened—cable TV attention-grabbing words—each time. But once we understand that we as a nation created the underlying conditions that enable these crimes, we can see why they happen with alarming regularity, and we can then enact reforms.

As I was interviewed about the Zimmerman case, I was often asked, “With all the shootings in America, why this case? Why has it garnered so much attention?”—as if an incident that occurs frequently is not newsworthy. To the contrary: if we have a persistent problem, we should talk about it more, not less. And what’s the implication of that question, that we are wasting time focusing on the killing of an ordinary citizen? Why not talk about this case?

The real answer: because we can only take them one by one. Pulling back and looking at the big picture, looking hard at all the people gunned down in America—especially young people of color—can lead to despair.

At least we are talking about one, I thought. We’re talking about it because Trayvon’s life was precious, just as every life is precious. We’re talking about it because it was not only tragic, it was preventable. And unlike most American homicide cases that don’t involve sexy white women or celebrities, Trayvon’s case was able to get some media attention. Tomorrow, let’s talk about another one. And another one after that.

Let’s talk about all of them.

And then let’s stop talking about them one by one, and let’s have an unflinching examination into why our society allows so many Trayvon Martins—gun homicide victims and racially profiled youth—to happen. And let’s start understanding where we’ve gone wrong, and then focus on known solutions that can help us save lives and become a less violent and more inclusive people.

NINE

“Everyone’s a Little Bit Racist”

“There is no immaculate perception.”

—FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

AFTER THE ZIMMERMAN verdict, some people, including Maddy the juror, expressed that our laws needed to be changed to prevent injustices like this one from happening in the future. And as we’ll see later in this book, some legal reforms would save lives and provide better accountability. But the first root problem is one so many deny exists at all: the persistence of racial bias in America. While we’d like to believe otherwise, we have not yet arrived at our goal of racial equality. But by understanding the way racial bias operates today—so different than a generation ago—and building on a solid body of social science research, we can propel ourselves much closer to that goal.

IN 1930, STANFORD sociology professor Richard LaPiere97 set off for a two-year road trip driving across the United States with his friends, a young Chinese couple. At that time, anti-Chinese sentiment was at an all-time high, with white Americans overwhelmingly in agreement with the California Supreme Court’s98 assessment that “They are a race of people whom nature has marked as inferior.” “Yellow peril” fears that the American way of life was at risk from Chinese immigrants bent on its destruction raged. Hundreds of Chinese had suffered lynchings in the preceding decades. Anti-Chinese riots erupted in Denver, Los Angeles, and other cities. Chinese Americans were run out of towns, forced to live in ghettos, and excluded from most jobs. The Chinese Exclusion Act, the only U.S. law ever to ban immigration based on race, prohibited immigration from China. The phrase “Chinaman’s chance,” meaning no chance at all, caught on after the conviction of a white man for murdering a Chinese railroad worker was overturned because all the eyewitnesses were Chinese.99

As a result of this hostile climate, LaPiere worried about being turned away from hotels and restaurants as he traveled with his foreign companions. He was pleasantly surprised, then, when they were politely received at virtually all of the sixty-six hotels and campsites and 184 restaurants they chose randomly along the route of their epic journey. In only one, “a rather inferior auto camp,” did the proprietor take one look at LaPiere’s friends and say, with the bigot’s typical imprecision, “We don’t take Japs!” (Happily, they promptly secured alternate lodgings that night at “a more pretentious establishment, and with an extra flourish of hospitality.”)100

But other than that one bad experience, LaPiere and the Chinese couple received overwhelmingly hospitable, friendly service across America. Sure, people were curious, especially outside the big cities, as many Americans at that time had never laid eyes on a Chinese national.

LaPiere reported that their curiosity generally turned into solicitousness, and he was delighted with the experience overall. His cheerful conclusion revealed how steeped even he was in the dehumanizing attitudes of his time:

A Chinese companion is to be recommended to the white traveling in his native land. Strange features when combined with “human” [why is this in quotation marks?] speech and actions seems, at times, to heighten sympathetic response, perhaps on the same principle that makes us uncommonly sympathetic towards the dog that has a “human” expression on his face.

Ah yes, the Chinese, like dogs, can seem almost human. This from a man who spent a great deal of his professional life analyzing and opposing his countrymen’s own unexamined biases.

For LaPiere was not just a traveler. His journey wasn’t simply a prolonged holiday; it was a social experiment, one with profound implications that launched a still-burgeoning field of social psychology.

Allowing six months to pass so that memories of his visits could fade, LaPiere then sent out questionnaires to each of the establishments he and his friends had visited, asking, “Would you accept members of the Chinese race as guests in your establishment?” Possible answers: “Yes,” “No,” or “Uncertain; Depend upon on circumstances.” With persistence, he obtained answers from 128 of the hotels and restaurants, about half of those they’d visited.

Remarkably, in the questionnaire answers, LaPiere received the opposite results from what he’d personally experienced. Ninety-two percent of the restaurant owners answered “No,” flatly denying that they would accept Chinese patrons. Ninety-one percent of the hotel owners also answered “No.” The remainder checked “Uncertain.” Only one out of the whole bunch answered yes, that Chinese travelers would be welcome, a female owner of a small campground who included a “chatty letter describing the nice visit she had had with a Chinese gentleman and his sweet wife during the previous summer.”

In answering LaPiere’s questionnaire, the Depression-era business owners overwhelmingly wanted to be seen as conforming to the accepted, overt racism of the day, reporting that no, of course not, they would not offer a room or a meal to Chinese customers. When presented with the very same situation months earlier, though, they had actually done so, with n

otable kindness, either because they decided to be decent and hospitable to their fellow humans (or “humans”), or because they wanted to earn a buck when they could. (Most of the time, upon arriving at a new establishment, LaPiere sent the couple in ahead of him, so that he could determine whether they’d be welcomed even without the presence of a white man as their companion.) As Albert Einstein said, “Few people are capable of expressing with equanimity opinions which differ from the prejudices of their social environment.” Einstein himself had been driven out of his native Germany around that time, his cottage turned into an Aryan youth camp, his books burned by the Nazis, his university position eliminated because he was Jewish.

LaPiere published his results in 1934. Don’t believe what people say in response to questionnaires, he concluded. If social scientists want to measure attitudes, relying on self-reporting is an ineffective way to go about it. The only way to know for sure how someone will behave in a given situation is to measure their actual behavior in that situation. We now know for sure, based on LaPiere’s classic work and the chain of research it spawned that continues to the present day, that our responses to questions may be wildly inaccurate and instead tend to parrot back the socially acceptable answer of our time. What we say and what we do are two different things. Sometimes this is because we know what we do, but we can’t admit it (we lie to others), and sometimes it’s because we are not consciously aware of our own behaviors (we lie to ourselves). Either way, asking people about their racial biases is as unreliable today as it was eighty years ago. The politically correct answer has changed, but our actions still speak louder than our words.

TODAY, ALMOST NO one will admit to racial animus of any kind. We profess to be egalitarian, to judge others, as Martin Luther King, Jr. admonished, not on the color of their skin but on the content of their character. Outside the world of extremists (Aryan Nation, skinheads, Neo Nazis), almost no one will call him-or herself racist. The word itself is a vile insult.

Suspicion Nation

Suspicion Nation