- Home

- Bloom, Lisa

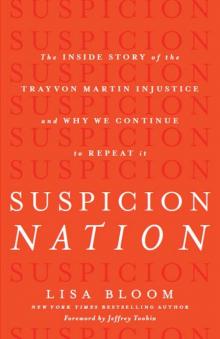

Suspicion Nation Page 14

Suspicion Nation Read online

Page 14

In the Zimmerman case, because they had the burden of proof, the state got to give two closings, their initial closing argument, and then, after the defense’s closing, a rebuttal closing argument. (This is common.) Two chances, sandwiching the defense’s argument. First and last, primacy and recency. From a rhetorical standpoint, a huge advantage.

But both of the prosecution’s final arguments were disasters.

First, the state’s summations were haphazard and disorganized. Instead of going through the elements of the crimes Zimmerman was charged with, second-degree murder and manslaughter, prosecutors did an odd hop, skip, and a jump through the evidence, going witness by witness, reminding the jury of a few points about each. But the jury had already sat through the trial, hearing each witness in order. They needed the salient points from each connected with the elements of the crimes alleged if they were to convict, and the prosecution did not give them that. As a result, though the elements of the homicide Zimmerman was charged with were simple, the jury wound up hopelessly confused about the law, walking away from the trial with wrongheaded interpretations of what they had to find in order to convict. Though de la Rionda briefly put up the law of manslaughter and murder an hour into his rambling, disjointed presentation, he raced through it, leaving the jury bewildered rather than enlightened on the rules they’d be required to follow to convict.

Second, for reasons only they can possibly explain, the state attorneys asked a series of questions in closing rather than using declarative statements to drive their case home. Far from demonstrating their own authoritative grasp of the evidence, the state seemed confused by the facts, resorting to telling the jury that they, the jurors, knew the trial, so hey, they could put it all together. For example, regarding the scratches on the back of Zimmerman’s head, de la Rionda said:

How small were they? You recall the testimony of the witness Miss Folgate. I think I had her tell me how big it was. I think she was … I mean it was hard to keep … anyway, you remember it.78

Had that stumble happened only once, one might chalk it up to a small mistake that could happen to anyone in a live trial. But over and over again, the prosecutor appeared not to have reviewed the evidence, and so he asked the jury to work it out themselves. Regarding the all-important crime scene map and time line, the prosecutor said:

You can see the map, you can track down the time line and see does it match up in terms of when he’s talking. I would submit to you again it doesn’t, but you rely on what the evidence shows.

After an exhausting three-week trial and sequestration, the jury is expected to go into the deliberation room and “track down” evidence and piece it together, when the state’s detectives and attorneys could not or did not? And what are they looking for, exactly? What supposedly doesn’t match up? And if it doesn’t, what does that mean? Reasonable doubt or a conviction? The message was hopelessly confused.

It’s the prosecutor’s job to fit all the puzzle pieces together for the jury in summation, to lead them smoothly along the primrose path to a guilty verdict. This isn’t just a style point. The message that shone through the state’s closing here was, If there is proof to support conviction, we don’t know where it is. Maybe you can find it. Good luck. This is unbelievably poor courtroom strategy, if it was an actual strategy rather than simple carelessness. I know of no other lawyers who have ever effectively handled a closing argument this way.

Issues big and small were handled with questions, not answers. On what should have been the biggest issue in the case, the prosecutor for the first time in the trial pointed out that Zimmerman’s gun was concealed behind him but then asked only, “How could the victim have seen the gun in the darkness?” First, calling Trayvon the “victim” throughout dehumanized him. He should have been called by his name. Second, questions invite speculation and multiple possible answers. Several spring immediately to mind. Since he’d been walking around for a while, his eyes had adjusted to the darkness? The fight was dynamic and he saw it when Zimmerman moved? Zimmerman’s jacket had ridden up, as he said? He saw the gun earlier in the fight, when they were close to the light? Questions imply reasonable doubt. Thus questions are a far weaker method of making a point than a definitive statement, like “Trayvon Martin could not have seen the gun. It would have been impossible. The gun was behind him and he was on his back, Mr. Zimmerman said. Mr. Zimmerman’s story is a lie. We now know this not only beyond a reasonable doubt, but beyond a shadow of a doubt.” If the state isn’t sure, how can the jurors be? If both sides are arguing reasonable doubt, an acquittal is the only possible verdict.

Third, devastatingly, the state failed to stand behind its own witnesses. De la Rionda used a PowerPoint presentation, in which he sometimes just put up a slide, scrolled through, and expected the jury to read and absorb it without comment from him, as though he’d gotten tired of doing a closing argument at all. One of his slides read, “SAO doesn’t choose Witnesses. Don’t go to central casting and order one up.” Using jargon or unknown abbreviations is another poor communication technique. What do you suppose SAO is? It took me a few minutes to figure out that acronym stood for state attorneys’ office. Were the jurors expected to know that?

More significantly, what was to be gained by slamming one’s own witnesses in closing arguments? Final arguments should be focused on convicting the defendant, not saving face for the lawyers. Prosecutors should have championed Rachel Jeantel, for example, reminding the jury not only that she was impressively good with dates and times, but also that the essence of her story never changed: that Trayvon feared the creepy man following him, tried to get away from him, and when confronted, said, “Why are you following me?” whereupon Zimmerman said, “What are you doing around here?” and then assaulted Trayvon—the reasonable inference to be drawn from Jeantel’s testimony that Trayvon’s headset was “bumped” and then she heard sounds of “wet grass.” Jeantel had familiarity with and a clear understanding of the sounds of Trayvon’s headset—she’d been on the phone with him all day, off and on. Trayvon’s final words were defensive, “Get off, get off.”

Credibility is the issue for every witness, the state should have explained. Credibility has nothing to do with skin color, gender, or size. It has nothing to do with a speech impediment or one’s hesitancy to be hurled into a courtroom on live TV, in the center of an extraordinarily high-profile case. If anything, Jeantel’s reluctance to be a part of this case bolsters her credibility, as she wasn’t rushing in to create a story or become famous. Believability should be measured by a witness’s truthfulness and integrity. Yes, Jeantel had fibbed about herself before trial (name and age to protect her privacy, and the white lie she gave to avoid going to Trayvon’s funeral), but she never wavered about what she heard on that phone call, and that’s why she is credible. She knew that some of the conversation she relayed would not be well received (creepy-ass cracka, nigga), but she put it out there honestly, warts and all. Plus, her testimony matches up with the cell phone records and even Zimmerman’s story—that Trayvon was running from him. She calls Zimmerman “a hard-breathing man,”79 and indeed, on his recorded police call, he is breathing heavily. Her story checks out, over and over again, because it is the truth.

Instead of doing that, the state considered Jeantel a throwaway witness by the end, offering several negative comments about her, and making only the weakest efforts to support her testimony.

Fourth, one of the state’s biggest failures was in not putting together all the evidence to show that Trayvon could not have seen and reached for the gun at the most critical moment in the altercation. As we’ve seen, a mannequin was available for use by the attorneys, but the prosecution’s use of it in closing was brief and clumsy. The state’s attorney straddled it for a few seconds, yelling, “How does he get the gun out?” Again, the question invited speculation rather than certainty. But we know that Zimmerman somehow did get the gun out, so the question went nowhere. The subject wasn’t how Zimmerman, trained

in the use of his own gun, and in the adrenaline of the situation, got it out. The issue—missed by the state at this most critical phase of the trial—was that Trayvon could not have seen it through the bulk of Zimmerman’s body, inside the back of his pants, behind him in the rainy darkness—and without that, Zimmerman’s selfdefense claim failed.

The prosecutor suggested that the jury get down on the floor in the jury room and reenact the altercation themselves (to see whether Zimmerman could get the gun out). Asking the jury to experiment was foolhardy. The jury might not do it, for any number of reasons, including the awkwardness of women who were strangers to one another a month earlier physically straddling one another. (In fact, they didn’t do it.) They might attempt it, but in an incorrect position, with no one there to correct them, which would throw the whole demonstration off. This is why it was essential that the prosecution, in closing, demonstrate every detail of it for them, with the gun in the concealed holster, the shirt and jacket, and even a patch of grass, reminding the jury of the darkness and the rain. And again, the issue was not whether Zimmerman got the gun out, because we all know he did. Instead, prosecutors had to prove that he did not have a legitimate reason to pull his gun. If Trayvon did not know that Zimmerman had a gun, and was not threatening his life, Zimmerman could not claim selfdefense.

Instead, the prosecutors spent a great deal of their precious closing argument time on tangents and nonissues. The prosecutors seemed to feel that being loud—for instance, yelling the self-evident “THE TRUTH DOES NOT LIE!” and repeating melodramatic uncontested facts like, “Two men were there that night; one is dead”—would suffice. Focusing primarily on Phase 1 of the story, the prosecutors repeated over and over again that Trayvon was unarmed, walking home from the store. I imagined the jurors thinking, Yes, we know that. No one has claimed otherwise. Please tell us why the shooting was murder. Because that’s what we have to decide.

The state insulted the jurors’ intelligence with red herrings like, “Buying Skittles is not a crime!” (Did anyone say it was?) “Trayvon Martin didn’t do anything wrong at the 7-Eleven. He bought that candy!” (Did anyone say he didn’t? Please tell me how that proves murder.) In his rebuttal closing, prosecutor John Guy called Trayvon a “child” dozens of times—this was jarring, as it was the first time in the trial anyone had done that. Technically, legally speaking, yes, Trayvon was a child. But most of us don’t think of a five-foot-eleven seventeen-year-old, especially one who clearly punched Zimmerman squarely in the face, as a child. Floridians don’t—they send kids younger than that to prison for life without parole sentences in record numbers. Either way, the issue was a distraction, a desperate new last-ditch effort to gain sympathy for “the victim,” whom the state had entirely failed to humanize during the presentation of evidence. And as Maddy recalled so vividly, the jurors were then instructed not to decide the case based on their hearts.

The theme of the state’s closing was that Zimmerman had told a “web of lies.” Going piecemeal through the evidence (rather than synthesizing it), they asked the jury to consider why Zimmerman had apparently lied about details of his story, such as his claim to police that he didn’t know what street he was on (the community only has three streets) or that he couldn’t see the nearest house number in the dark. But most people in a stressful situation will forget commonly known information, and minor inconsistencies in retelling the same story are understandable. The bigger problem was that Zimmerman was not on trial for lying, he was on trial for murder. So the prosecution needed to connect Zimmerman’s “web of lies” with the murder charges, and they never did so.

“This case is not about Standing Your Ground,” Guy said. “It’s about staying in your car.”80 A nice rhetorical flourish—the state had a few of those—but Zimmerman was not on trial for getting out of his car, even though the police told him not to, nor for walking around the neighborhood looking for Trayvon. Nor could he be, as none of these acts are illegal, which everyone conceded by the end of the trial. He was on trial for murder, and the prosecution throughout seemed unwilling to confront that charge. Pointing out Zimmerman’s falsehoods and ugly words was a step in the right direction, and relevant to the element of intent, but was not sufficient to get a conviction.

Sure, some of Zimmerman’s lies were big. His head could not have been banged on concrete at the time of the shooting, as his body was a substantial distance from concrete. In addition, no blood was seen on the sidewalk when crime scene investigators looked that night. And Zimmerman had blood dripping off both the front and back of his head when photographed immediately after the shooting (from the punch to his nose, and from two tiny cuts on the back of his head), so one would expect to see blood on the concrete if his head had been slammed into it. The state should have argued not only that Zimmerman lied, but that his lies meant his version must be rejected entirely as not credible, and then invited the jury to come along with the state’s theory of the case, supported by the evidence and reasonable inferences from that evidence. But the prosecution offered no alternate scenario.

And that was the state’s biggest blunder in summation: its failure to offer its own theory of the case. For the most part, as they had throughout the trial, prosecutors went along with the defense’s version of what happened that night, arguing only the details around the edges. For example, the state attorney wondered how Trayvon could have put his hand over Zimmerman’s mouth, as Zimmerman had maintained, and simultaneously pounded his head on the cement. Since he could have done one then the other in rapid succession, this weak argument went nowhere, and as we’ve seen, wondering equals reasonable doubt. The visual the jury was left with was that Trayvon punched Zimmerman, he went down, Trayvon banged Zimmerman’s head on the concrete, saw and reached for the gun, and then Zimmerman drew his gun and killed him—the defense story.

The jury sorely needed an alternative, one that the state could have easily put together for them by pulling out the key testimony from its own witnesses. Such as:

Members of the jury, we know what really happened that night. When the defendant got out of the car to confront Trayvon, he was convinced that Trayvon was an armed criminal, and he wanted to keep him there until the police arrived, so that he didn’t get away like all the other “fucking punks.” We know that from Zimmerman’s own recorded words. So what did he do, alone, on that dark night, when he went after him? What’s the reasonable inference? He drew his gun. Trayvon saw the gun all right, but not in the way Zimmerman told it. We know from two defense witnesses, Adam Pollack and Dennis Root, that Zimmerman had no physical fighting skills whatsoever. He was a one on a scale of one to ten in his martial arts class. He was overweight and not athletic. And he knew it.

Which is precisely the reason he carried a gun, to compensate for that deficit. Many of us keep guns in our homes for selfdefense, but few of us walk around with concealed weapons when we’re going to Target.

But unfortunately for Trayvon Martin, George Zimmerman was a man who regularly lived in unreasonable fear. We know from his prior police calls about other black men in the neighborhood that he didn’t want to go near them. He didn’t want to approach “suspects.” Zimmerman feared African-American men in his neighborhood. All of his police calls about suspicious persons in the prior six months were about black men, even though the community is 20 percent African American. Never mind that, they’re all suspicious! And here was another one, walking down the street. Trayvon Martin, a “real suspicious guy.” Zimmerman’s ill will toward Trayvon was instantaneous, his decision that he must be a criminal so conclusive that he didn’t want to give the police dispatcher his address for fear Trayvon would hear it and come after him. And we know that Zimmerman did not want him to escape—“These assholes, they always get away.” This one, this time, was not going to get away.

He told the police Trayvon was reaching into his waistband (the inference being that Trayvon had his own weapon—another reason Zimmerman was scared). Like so much of what Zimmer

man said that night, this is an exaggeration or an outright lie. Because Trayvon had no weapon.

Listen to what Rachel Jeantel told you about the moment when Zimmerman and Trayvon met. She heard the exchange, and she’s the only one who did. Trayvon asked a reasonable question, “Why are you following me?” A respectful answer would have been, “Hey, I’m Neighborhood Watch, so just wondering if you live here or you’re visiting someone?” “I’m staying over at Brandy Green’s, that house on the end,” Trayvon would have said. And that would have been the end of it.

Instead, Zimmerman, hopped up on the ill will he harbored toward a lot of black males walking down the street in his community, responds with the hostile, “What are you doing around here?” Zimmerman then grabs or shoves him, because Rachel Jeantel hears a thump on the headset clipped to Trayvon’s hoodie. That thump means Zimmerman touched him, without Trayvon’s consent—an assault. At that point, Trayvon, surely frightened, has every right to defend himself and stand his ground, so he lands one good punch to Zimmerman’s face. A tussle ensued, where it’s not particularly significant who was on top and who was on the bottom at any given point. We know that Zimmerman’s “Trayvon saw the gun through my body” story is preposterous. We know that Zimmerman had to draw his gun while standing or while he was on top, because it’s physically impossible while he’s down. Zimmerman drew his gun early in the incident because he was afraid, because he didn’t want Trayvon to get away, because he wanted control over the situation. The most reasonable inference to draw from the evidence is that he drew it when he approached Trayvon initially. With the gun pointed at Trayvon, Zimmerman likely continued the profane insulting rant he started on his police call, for a horrible forty seconds, as Trayvon screamed for help, hoping this armed madman would not do the unthinkable.

Suspicion Nation

Suspicion Nation