- Home

- Bloom, Lisa

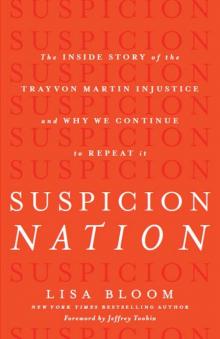

Suspicion Nation Page 12

Suspicion Nation Read online

Page 12

Yet Jeantel’s speech patterns, because they are associated with poor African Americans, were perceived by many, including the people who mattered most, the jurors, as unintelligent, and worse, evidence that she was not credible. In fact, she used a common dialect spoken by millions of Americans, with its own intricate rules of grammar and pronunciation. When young people like Jeantel grow up in communities where this dialect is spoken, they are told in school to “speak properly,” belittling their community’s tongue and pressing them to learn a second set of grammar and vocabulary rules, at least in school, which many do. (Most of Jeantel’s testimony was in “proper” American English, so she was capable of switching back and forth.)

Linguist John McWhorter defended Jeantel’s speech:70 “It’s Black English, which has rules as complex as the mainstream English of William F. Buckley. They’re just different rules. If she says to the defense lawyer interrogating her, ‘I had told you,’ instead of, ‘I told you,’” it’s because “black people around the country use what is called the preterite ‘had.’”

Intelligence had nothing to do with it. She was able to easily and accurately identify names and complex relationships (Chad Joseph was Trayvon’s future stepbrother; Trayvon was staying in the home of his father’s fiancée). Dates and times were readily available to her—unusual for most witnesses, who couldn’t possibly tell you the date something happened more than a year before, much less the precise time. Handed a page of phone records, she immediately corrected the exhibit, saying that she had spoken to Trayvon beginning at noon on February 26, 2012, yet the records showed that her first call was at 5:09 PM. She recalled the exact date she and Trayvon had begun texting and speaking on the phone frequently, February 1, 2012, and that March 17, 2012, was a Saturday. In each of these statements, remarkably, she was correct. In addition, we learned later that she was trilingual, speaking Haitian Creole and Spanish. She was fluent in more languages and dialects, then, than 90 percent of Americans.

But none of that came out clearly because her dialect and diction were difficult for the jury to understand. Worst of all, the jury heard from her for the first time in the trial, without explanation, two loaded racial terms—and they were attributed to Trayvon Martin. Jeantel said that when she asked him to describe the man who was following him, Trayvon said he looked like a “creepy-ass cracka.” “What?” said some of the jurors. “Creepy-ass cracka.” She was made to repeat the phrase several times so the court reporter could get it down, defense could hear, judge could get it, etc. A few minutes later, describing Trayvon’s reaction when he thought he’d lost Zimmerman, only to have him reappear, Jeantel quoted Trayvon: “The nigga is still following me.” WHAT? WE CAN’T HEAR. WE CAN’T UNDERSTAND, clamored the jurors, in a rare moment of speaking aloud in the courtroom from the jury box. She said it again.

“Forgive me—nigger? The N word?” Bernie de la Rionda gingerly offered. “That’s slang,” Jeantel began to explain, but she wasn’t given the opportunity to say more, as the prosecutor was eager to move on.

Sitting in the jury box, Maddy felt bad for Jeantel, having to repeat her testimony so many times. Her language didn’t faze Maddy a bit. She’d heard it all before. Some of Maddy’s kids were teenagers close in age to Trayvon and Jeantel. “I hang with a young crew,” she told me. “When you do, you learn slang.”

All the other jurors, though, were offended by “creepy-ass cracka,” Maddy said, and they were done with Jeantel once they heard that. When Jeantel used the word “nigga,” other jurors turned to Maddy, asking her, “What did she say? Nigger? Isn’t that a racist word?” Why are they asking me? Maddy wondered. Because I’m black?

Maddy had an entirely different view. “Nigga,” she knew, was different from “nigger,” the former being a slang word among some minority youth comparable to “dude,” a word that can apply to anyone of any race. The latter is a highly offensive word when uttered by non–African Americans. “How is she racist?” Maddy said to me later, “She’s black, and she’s using the word ‘nigga’ about a white man.” In the jury box, Maddy thought, here we go again, feeling marginalized, her community misunderstood.

“I love Rachel Jeantel!” Maddy told me later. “I love her because I understood her. I understood what she was saying.” But the other jurors did not.

To understand Jeantel’s testimony, one must perform an exercise not available to the jury: sit in a quiet room, watch the video of her answering the courtroom questions multiple times, translate some of her dialect for those not familiar with it, eliminate the large amount of repetition, and cut

out the constant stream of objections, comments, and courtroom distractions, which Jeantel was bombarded with far more than any other witness at the trial. The jury even had to be admonished to stop speaking aloud during her testimony, but instead to raise their hands if they had a problem.

That exercise reveals the essence of what Jeantel was trying so hard to say about her final phone call with her friend Trayvon, which the jury never got to hear with any clarity:

He kept complaining that a man was watching him. He said the man looked like a creepy-ass cracka.

I told him the man might be a rapist.

Trayvon said, “Stop playing with me.”

I told him OK, then why does he keep looking at you?

Trayvon said he’d try to lose him, and then he calmed down a little bit.

Then he told me the man was following him.

He started walking home. He said he was leaving the mailing area, which is where he was.

Then we started talking about the All Star game. He told me to go check for him if it was on.

Then Trayvon said, “The nigga is still following me.”

I told him to run.

Trayvon said, no, he’s almost by his daddy’s fiancée’s house.

Trayvon said he was almost there, but he was complaining that the man was still following him. Then he told me that he was going to run from the back. Then I heard wind, and the phone shut off. I called back, he answered.

I asked him where he was.

He told me he was in the back by his daddy’s fiancée’s house. He said he lost him.

I told him keep running.

A second later, Trayvon said, “Oh shit, the nigga behind me.” I told him he better run. He was almost by his daddy’s fiancée’s house.

Then I heard Trayvon say, “Why are you following me for?” Then I heard a man, breathing hard, say, “What are you doing around here?”

I started saying, “Trayvon,” then I heard a bump, which was his headset. Then I heard wet grass sounds. I was calling, “Trayvon, Trayvon.” I kind of heard Trayvon say, “Get off, get off.”

The phone then shut off. I called him back. He didn’t answer, and I never spoke to him again.

The poor presentation of Jeantel’s testimony meant the jury missed the fact that Trayvon was in fear of Zimmerman throughout, repeatedly tried to lose him, and was running back home to escape Zimmerman, trying to get away from him. At one point, he thought he’d lost Zimmerman, and he returned to talking about the basketball game—not, “I’m going to find and kill that guy,” not, “I’m going to hide in the bushes, Rachel, and then jump out at him,” but, “Hey, go check and see if the game has started yet, I don’t want to miss it.” Jeantel’s story directly contradicts much of Zimmerman’s, but so little of it got to the jury in any understandable way.

Jeantel also said that it was Trayvon’s voice screaming on the Lauer 911 call, without elaboration. None was asked of her by the prosecution. (Later on cross-examination, we learned from Jeantel that Trayvon sometimes had a “baby” voice. The man’s screaming on the call was high-pitched. Only lack of preparation by the prosecution would have left this corroborative detail out of her direct examination.)

After the trial, speaking to CNN’s Piers Morgan, Jeantel was permitted to explain those explosive terms she said Trayvon had used about Zimmerman. “Cracka” was the word, not “cracker,�

� she said, and it means a cop or security guard and is not racial in her view. (And indeed the term “cracker,” according to UrbanDictionary.com,71 originates from slave owners “cracking the whip.” The first definition, however, is “a term used to insult white people.”)

Because the prosecution did not understand Jeantel’s dialect, and was too afraid to linger on anything related to race in the case, it missed an opportunity to diffuse these terms for the jury, who predictably were surprised and affronted by them. In this racially charged trial, the prosecutor should have neutralized the language on direct examination.

This is how the practice should have gone, during witness preparation:

PROSECUTOR: What did he say next, Ms. Jeantel?

JEANTEL: He said nigga following me.

PROSECUTOR: He said what?

JEANTEL: Nigga following me.

PROSECUTOR: You mean, the N word? Trayvon said that about Zimmerman? But Zimmerman’s white, so I don’t get it.

JEANTEL: Oh, the way we use that word isn’t the way you use it.

PROSECUTOR: I don’t use it at all!

JEANTEL: Okay, chill. I just mean, it’s not racial. “Nigga” is just a guy, like “homie” or “dude.” “Nigga following me” just means the guy [Zimmerman] was back, following him.

PROSECUTOR: So it’s not a racial slur?

JEANTEL: Naw, he was talking about a white man so how could it be? How could he be both a “cracka” and a “nigga” if both the terms are racial? That doesn’t make any sense. It’s just how we talk. Like in our music and movies. Trayvon didn’t know his name, so he’s just “nigga.” Maybe you would say “the guy.”

PROSECUTOR: I think I understand. So when you testify, when we get to this part, please, Rachel, say it slowly and clearly, because that’s going to freak some people out who aren’t used to hearing the word the way you use it. And then I’m going to ask you what that word meant as you understood it in your conversation with Trayvon, and you explain it as you just did. OK?

JEANTEL: Yeah, if that’s what you want.

PROSECUTOR: Trust me, this is important. Now let’s go back and go over it again so that when you speak to the jury your testimony will be clear. Let’s take it from the top.

JEANTEL: Aw, do we have to?

PROSECUTOR: Yes, Rachel, we do. We are going to go over this until your testimony is clear, so that the jury can understand it when you get up on the witness stand. Can you do that for Trayvon?

JEANTEL: Well, when you put it that way, yes. Okay, let’s practice again.

They go over it again. And if necessary, again and again.

AFTER HALF AN hour on the stand being questioned by Bernie de la Rionda, Jeantel was not done. Not even close. To her horror, she then endured five hours (over two days) of cross-examination questions from West. He went over her entire story again, in painstaking detail, as well as the lie she’d admitted to on direct—to get out of going to Trayvon’s funeral she’d told his family she was in the hospital—and several others, all of which were lies about herself in clumsy attempts to get out of being involved in the case. She’d said she was sixteen, rather than her true age at the time, eighteen, when initially contacted about the case. She’d given nicknames, Dee Dee and Diamond, rather than her real name, in an effort to protect her privacy. None of that worked, of course, and here she was, on the stand, being interrogated, analyzed, and judged by the nation.

The prosecution badly misstepped by not bringing out all of Jeantel’s fibs on direct, allowing her to explain them with a friendly questioner. Instead, on West’s cross-examination, Jeantel came across like a pathological liar, one false statement after another being thrown at her. A jury might understand making up a story to get out of a funeral (“I didn’t want to see the body,” Jeantel said on the stand, wiping her eyes), but the others, piling up, began to sound like a pattern.

Throughout the trial Judge Nelson indicated a willingness to move the testimony along whenever attorneys were long-winded, repetitive in their questioning, or prone to going off on tangents. While West was all of these during his cross-examination of Jeantel, de la Rionda rarely objected, leaving Jeantel on her own to handle West, a man who’d been cross-examining witnesses longer than she had been alive. Nitpicky questions on irrelevant topics—such as detailing how her meeting with attorney Crump was set up, or texts leading up to a media interview, or the scheduling and rescheduling of her deposition—went nowhere, but Jeantel had to wrack her brain, stay calm, and try to answer, as the prosecution sat mutely by. Despite Jeantel’s clear testimony that she was not Trayvon’s girlfriend but just his friend, West asked her many questions, without objection, as to whether that was really the case. (She maintained her position throughout and he never got anywhere with it.) Judge Nelson surely would have instructed West firmly, in front of the jury (as she did on other occasions) to move it along, if only the state attorneys had risen to their feet.

After several hours on the stand and the seemingly endless, repetitive questions from West, Jeantel, feeling disrespected, got testy. She muttered that she was leaving at the end of the day and not returning the next. Despite seeing that the teenager’s nerves were frayed, the prosecution did not offer her a break nor ask the court for one. They let her twist in the wind.

False bravado notwithstanding, she did return, and on the next day, she arrived preternaturally calm, adding “sir” to her answers to boot. Trial watchers speculated that the prosecutors must have sat her down and explained to her that her demeanor needed to change, shoring her up for her second day to come. But that would be giving the state attorneys too much credit. Left on her own after her first day of testimony, what actually happened, Jeantel says, is “I went to my room, said my prayers, said, OK, this is for you, Trayvon.”72 She resolved to keep going, for him. On a more practical note, her attorney, Vereen, told me that he decided to get her out of the painful, pinching high heels she’d been wearing on the first day, and he purchased a better pair of shoes for her second day, so she could be more comfortable. (Now that’s a full-service attorney.)

Jeantel told me that contrary to popular belief, no one spoke to her about her demeanor that night. “I was just so tired, worn out,” she said, after spending the day being cross-examined by the man defending her friend’s killer. She went back to her hotel room, “no cell phone, no TV, oh my God!” she said in teenaged disbelief, and went to sleep. Clearly the good night’s rest improved her testimony, as she was markedly calmer, more relaxed, and more respectful the next day. Unfortunately, though, much of the damage had already been done.

ON CROSS-EXAMINATION, WEST went after Jeantel for varying her account of what happened in different statements she’d given. By the time of trial, Jeantel had given a dizzying number of pretrial statements to different people in different contexts: among others, to Tracy Martin, who first contacted her, to Sybrina Fulton, to Crump, to the police, and to the lawyers present during her deposition. This was not a problem created by Jeantel, who at all times was trying to extricate herself from having to give statements, but rather by the police’s failure to contact her immediately in their investigation of Trayvon’s shooting, their failure to discover the important testimony she had to offer, their failure to get one clear pretrial statement from Jeantel and then direct her to give no others. Though phone records would have quickly revealed that she was speaking with Trayvon in the minutes before his death, inexplicably, police did not contact her, leading them to initially conclude that Zimmerman’s statement was consistent with all the evidence. Thus Trayvon’s family had to pick up the ball, contact Jeantel, and plead with her to share the information she had.

These multiple interviews contained some inconsistencies, as nearly always happens when a witness tells and retells her account. (This is why lawyers favor long, detailed depositions of opposition witnesses, to undermine their credibility.) In her case, that was especially true as she was traumatized by her teenaged friend’s death and was trying to

be polite to his grieving parents, which meant leaving out some details in an effort to spare them more pain. In addition, in early accounts Jeantel gave quick summaries of what she knew, in order to minimize her role in the situation, which was then emerging as a high-profile matter that she wanted nothing to do with. As she was asked later exactly what Trayvon said and what she said on the call, more details in her story emerged. The defense called this embellishing, but her story overall remained consistent.

The defense also grilled Jeantel about her view that the altercation between Zimmerman and Trayvon was “just a fight” and not “deadly serious”—which was her initial opinion after hearing the sounds of wet grass and then her call dropping. But the opinions of fact witnesses are not admissible—especially when she’s speculating what happened after her connection with Trayvon failed. The prosecution failed to object to this, so it came in.

However, on redirect examination, when they had a chance to question her again, the prosecution could have exploited this topic by allowing her to explain: Trayvon didn’t express anything to her about planning to attack, much less kill, Zimmerman. He wanted to go home and watch the All Star game and get away from Zimmerman. So the sounds she heard at the end of the call with him—words exchanged, Trayvon’s headset getting bumped, the sounds of wet grass—sounded to her like the beginning of a fight, not something deadly. Her testimony on that point was entirely consistent with the state’s position that Travyon did not intend to assault or kill Zimmerman. Put another way, if Trayvon had told her, “I’m going to kill that guy,” she would have been alarmed when the call dropped. She wasn’t, because it sounded to her like at most, “just a fight.”

And that should have been the essence of Jeantel’s testimony to the jury: that Trayvon was doing the opposite of what Zimmerman claimed. He wasn’t gunning for a fight. I asked Jeantel what kind of mood Trayvon was in on that phone call. “He was funny,” she told me. “He was cracking me up most of the call.” Trayvon’s sense of humor was one of her favorite things about him—that and his loyalty to his friends. She was doing her hair at home while Trayvon was walking through the Retreat at Twin Lakes, and he was teasing her about her hair obsession: “You’re gonna die with those hot rollers on, Rachel!” She laughed, he laughed. He asked her to check on whether the All Star Game had started yet, and she did. The prosecution was so stuck in the weeds (He said what? And then you said what?) that they missed the overarching theme Jeantel could have described for the jury: these were two high school kids having a lighthearted, jokey chat, even after Trayvon saw Zimmerman staring at him. Far from lying in wait for him and jumping out of the bushes to sucker punch him (as Zimmerman described in one of his versions of what happened), Trayvon wanted to get away from the “creepy” guy and go back home to catch the game and continue teasing Jeantel.

Suspicion Nation

Suspicion Nation